The 1855 Bordeaux Classification, Part I: Genesis of a Market-Making Hierarchy

- marclafleur3

- Jan 28

- 5 min read

A list that became a regime

The most powerful financial tools don’t always look like finance. Sometimes they look like a simple list.

The 1855 Classification is often presented as a dusty historical artefact, a relic from a vanished world of emperors, carriages, and sealed letters. But in the reality of the fine-wine market, it functions more like infrastructure: a durable system that compresses complexity into something instantly readable. And when a market can read something quickly, it can price it quickly. That’s not romance, it's liquidity.

This is why 1855 still matters for wine investment. Not because it is perfectly “fair.” Not because it is scientifically “true.” But because it created a hierarchy that the world accepted, and kept accepting, generation after generation.

Paris, 1855: prestige as policy

The Exposition Universelle as geopolitical branding

To understand the classification, you have to walk into Paris first.

In 1855, Napoleon III staged the Exposition Universelle on the Champs-Élysées, a world’s fair running from 15 May to 15 November 1855, with the explicit goal of displaying French excellence in agriculture, industry, and the arts. The fair was not only cultural; it was geopolitical branding. It was France saying: we are modern, we are refined, we are the center.

The theatrical tone mattered. Awards were handed out in the Palais de l’Industrie in the presence of the Emperor and Empress Eugénie. This was not a neutral showcase; it was imperial messaging — excellence presented as order, and order presented as destiny.

Wine as the most portable form of prestige

And wine was an unusually effective messenger. A machine can be admired and forgotten. A bottle can be purchased, stored, served, gifted — carried into other countries’ dining rooms and boardrooms. Wine travels as prestige. In 1855, France didn’t just want to impress visitors; it wanted to export admiration.

So Napoleon III asked the country’s wine regions to produce classifications of their best wines for the exposition. In Bordeaux, the request would trigger something far bigger than the organisers could have predicted.

The City of Light as an energy system

Paris itself was part of the argument. The city was being rebuilt into a statement of power and competence — broader boulevards, cleaner circulation, a capital that looked like it could manage the future.

Even its illumination was part of the message, and it was industrial. Under Haussmann, the city’s underground networks expanded: sewers, water, and especially gas lighting, which surged in these years. The night-time city became a controlled spectacle of modern comfort: safer streets, brighter avenues, a sense that the state could tame darkness.

And that light had a source. In the 19th century, “town gas” was produced by distilling coal — an urban energy technology that depended on supply chains and transport to feed the city’s appetite for brightness. Paris’s glamour, in other words, ran on fuel.

The industrial century’s obsession: standards, systems, readability

Why modern trade needed hierarchy

The mid-19th century is the age when modern society becomes obsessed with systems: rail networks, timetables, measurements, statistics, catalogues. The deeper story behind 1855 is that Bordeaux is doing what modernity does: turning complex reality into an organised interface.

Wine is inherently complex. It’s agriculture plus weather plus human judgement plus time. Yet global trade requires something legible. Buyers in London, Amsterdam, Saint Petersburg, or New York cannot simply “feel” terroir from a distance. They need signals, not perfect truth, but a stable language of trust.

Classification as friction reduction

A classification is exactly that: a standardised narrative that travels faster than nuance. In investment terms, it reduces friction. It lowers the mental cost of decision-making. It creates a ladder where people can place their money and feel they understand what they own.

This is where the 1855 Classification becomes more than a historical curiosity: it becomes a tool that industrial society was already craving.

Bordeaux was already global — and very commercial

Courtiers, négociants, and the machinery of trust

Bordeaux didn’t invent trade in 1855. It formalised what it had been practising for a long time.

Unlike regions built around tiny domaines selling locally, Bordeaux had a mature commercial ecosystem: courtiers (brokers) and négociants (merchants), plus an export culture wired into the identity of the place. The classification did not come from a romantic circle of tasters; it came from the professional intermediaries who lived inside the market every day.

That’s why the Chamber of Commerce could simply ask the brokers to rank the region’s best wines — and expect a usable answer quickly.

Reputation → price → distribution

In other words: Bordeaux had something priceless long before 1855 — not only great vineyards, but a distribution and information machine capable of translating quality into reputation, and reputation into price.

The classification didn’t create that mechanism. It gave it a seal, a stage, and a form the world could absorb at a glance.

The two-week invention: how the list was made

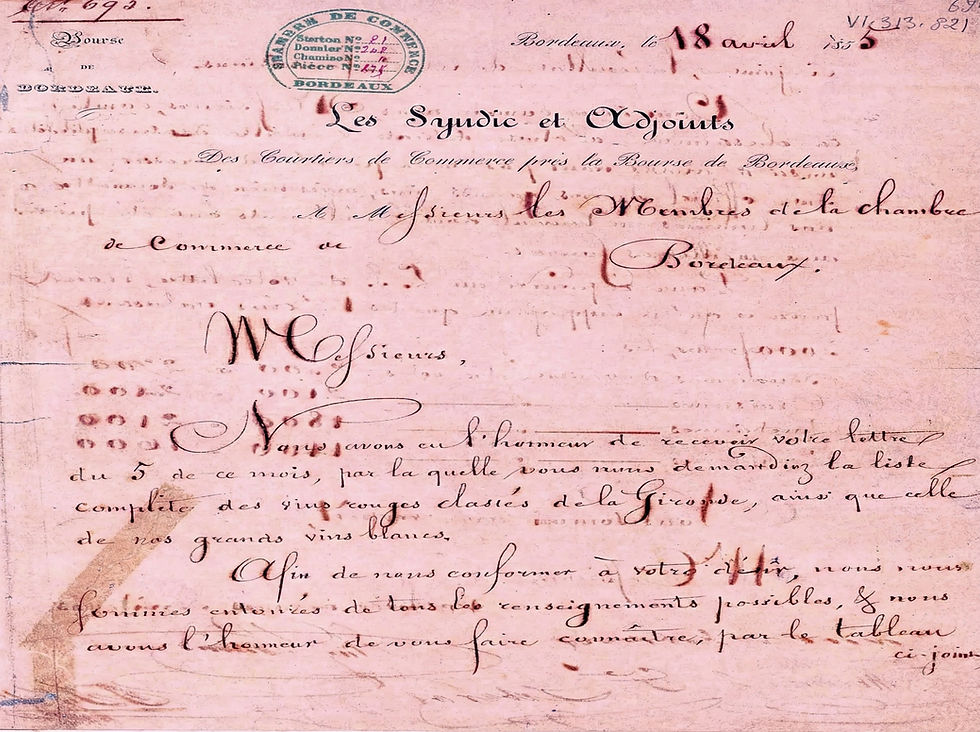

April 5 to April 18: codifying what the trade already knew

Here’s the part that still feels almost shocking: it happened fast.

The process began with a formal request on 5 April 1855 and the brokers compiled and submitted the ranking by 18 April, about two weeks later.

How can something that still shapes markets today have been assembled in a matter of days?

Because the classification didn’t come out of nowhere. It was essentially a snapshot of what the trade already knew, codified into a neat hierarchy that could be displayed to the world.

Price as proxy, and the genius of usefulness

The method was market-driven: wines were ranked according to reputation and trading price, which at the time were treated as reliable proxies for quality. Not because price is holy — but because price is a social fact: it contains the memory of transactions, the weight of consensus, the repetition of desire.

This is the key historical nuance that many people miss: the classification wasn’t created to discover excellence. It was created to display excellence. It didn’t invent Bordeaux’s reputations; it canonized them.

And it canonized them in a language the world understood immediately: tiers.

From imperialism to wine investor’s benchmark

Napoleon III’s quest for grandeur

Could it be that the 1855 Classification, now one of fine wine’s ultimate reference points, sprang from the same thirst for grandeur that would later steer Napoleon III toward catastrophe at Sedan in 1870? Expansionism and the exercise of power were never far from the Emperor’s imagination. He left an indelible mark on history, for better and for worse.

It’s easy to picture him lingering over the map of Europe, day after day, mentally redrawing its contours to match an ambition that never quite found an edge. Power as a guiding thread. France would lead the world — and its great wines would travel as proof. But did he suspect that this imperial instinct for display would give birth to a hierarchy the market still trusts, almost two centuries later?

Hierarchy as investor's compass

The Exposition Universelle was not simply a celebration of industry and culture; it was a geopolitical stage. Presenting Bordeaux through a ranked list offered France a clean, authoritative story to tell international visitors: we don’t merely produce wine — we produce excellence, structured, ordered, and unmistakably French. A hierarchy is persuasive because it feels like certainty.

The list did not come from blind tastings or philosophical debates about terroir; it came from brokers and from prices. By elevating the market’s internal consensus into an official ranking, the classification gave commercial reputation the dignity of state endorsement. It turned trade knowledge into institutional truth.

The 1855 Classification is a market maker, a durable insrument that defines legitimacy, concentrates attention, and decides which names become the world’s shorthand for greatness.

Comments