The Rise of Alternative Investments and the Benefits of a Diversified Portfolio

- marclafleur3

- 7 days ago

- 13 min read

Fine wine, real estate, cars, watches, and art—what they really add, what they quietly cost, and how to think about them like an investor.

Walk into any private bank, family office, or serious wealth conversation today and you’ll hear the same quiet refrain: “We need more diversification.” Not more products. Not more cleverness. More diversification—meaning exposure to return drivers that don’t all react the same way when rates spike, liquidity dries up, or sentiment flips.

That shift is one of the defining capital movements of the last decade. Alternatives used to be a niche corner—something you did for pleasure, for legacy, or because you had a friend who “knows the market.” Today, alternatives have matured into a deliberate portfolio sleeve: professionally selected, risk-managed, and increasingly measured.

The simplest proof is where sophisticated capital is already allocating. UBS’ Global Family Office Report 2025 shows that alternatives are not a side dish: U.S. family offices allocate 54% to alternatives, and family offices globally average 44% in alternatives (2024).

This article is not an invitation to chase “the next hot collectible.” It’s a framework: how fine wine, real estate, collectible cars, watches, and art can contribute to a diversified portfolio—and the pitfalls that usually separate a good allocation from an expensive hobby.

What “alternative investments” really means now

Alternatives are often defined by what they are not: not public equities, not plain-vanilla bonds, not cash. But that definition misses the point. What matters is not the label; it’s the economic behavior.

Alternatives tend to share three qualities:

Different pricing mechanics

Many are not continuously marked like stocks. That can be a benefit (less noise) or a risk (you only discover the real price when you must sell). With art, this is almost the entire game; with wine and watches, pricing is more observable, but still fragmented. With real estate, pricing can be transparent in some markets and deeply opaque in others.

Real-world constraints

Scarcity matters—land, production, aging curves, vintage variation, physical uniqueness. In wine, supply is literally consumed; in art, supply is constrained by an artist’s lifetime output and institutional validation; in prime real estate, land is the hard ceiling.

High dispersion

This is the most important part. The spread between the winners and losers is often much wider than in traditional markets. “The art market” is not a market. It’s a constellation of micro-markets. The same is true for watches, cars, and wine. Indices are useful as thermometers, but selection dominates outcomes.

The rise of alternatives is also visible in broader wealth research. Knight Frank’s Wealth Report tracks both real estate and “luxury assets” behavior and shows how tangible assets remain central to private wealth decision-making.

The point isn’t that watches or fine wines are “better than stocks.” It’s that investors keep looking for assets with different risk sources and different cycles.

The real point of diversification (and the mistake people make)

Diversification is often marketed as comfort: “own more things and you’ll be safer.” In reality, diversification is closer to humility. It’s the acceptance that the future will not respect your favorite scenario, so you build a portfolio that can survive multiple regimes.

Done properly, diversification means combining assets whose returns are driven by meaningfully different forces: cash flows, scarcity, replacement cost, cultural demand, time-based supply shrinkage, and in some cases simple monetary behavior.

The common mistake is to treat alternatives as “decorrelation machines.” They are not. In stress periods, correlations can rise across everything that feels discretionary or luxury-adjacent. We saw that in the cooling of several collectible categories after the post-pandemic surge. The lesson is not “avoid alternatives.” The lesson is: be honest about what kind of alternative you’re buying.

Some alternatives are closer to “income and inflation linkage” (real estate). Some are closer to “brand + scarcity + social demand” (watches, certain wines). Some are closer to “curation and access” (art). Your diversification improves when your alternatives sleeve is internally diversified, not when it is simply “different from stocks.”

A practical framework to judge any alternative

Before we touch each asset class, here is the checklist that keeps you out of trouble. It’s not theoretical. It’s what separates professional allocation from enthusiastic collecting.

1) What is the return driver?

Is this an income asset (rent)? A scarcity asset (limited supply that tightens)? A cultural asset (taste and status)? A quality asset (proven longevity of demand)? If you can’t articulate the driver in two sentences, you don’t own an investment—you own a story.

2) How liquid is it, really?

Liquidity is not “can I sell?” It’s “can I sell at a fair price in a reasonable timeframe?” Watches can be liquid for top references; art can be functionally illiquid unless you accept auction timing and fees. Wine can be surprisingly liquid when it’s blue-chip and perfectly stored; it can be painfully illiquid when it’s the wrong selection.

3) How reliable is price discovery?

Do you have an index, observable transactions, auction records, merchant pricing, or are you relying on dealer quotes? Liv-ex provides structured index data for wine. WatchCharts does something similar for the secondary watch market. Art has public auctions, but a meaningful share of the market is private, which makes transparency uneven.

4) What are the carry costs?

Carry costs are the silent decider. Storage, insurance, maintenance, servicing, taxes, restoration, vacancy, financing. They don’t just reduce returns; they also shape your ability to hold through downturns.

5) How wide is the bid–ask spread?

The spread is the price of illiquidity and friction. Collectibles often have larger spreads than investors expect, especially outside the “top 1%” references.

6) What is the authenticity/provenance risk?

Wine provenance can be excellent with bonded storage; it can also be a minefield with weak documentation. Watches face counterfeit and parts-swapping risk. Art faces attribution and authenticity risk that can destroy value.

7) What is the “enjoyment yield”?

This is not a joke. One reason alternatives work for long holding periods is that some owners derive real utility while holding—living in a property, enjoying a collection, opening bottles. But enjoyment yield only helps if you bought sensibly. Overpaying converts pleasure into regret.

Keep this framework in your pocket. Now let’s go asset by asset.

Fine wine: scarcity you can measure, time that does the work

Fine wine sits in a special place among collectibles because it combines cultural demand with a surprisingly investable infrastructure: professional storage, established trading networks, and widely referenced benchmarks.

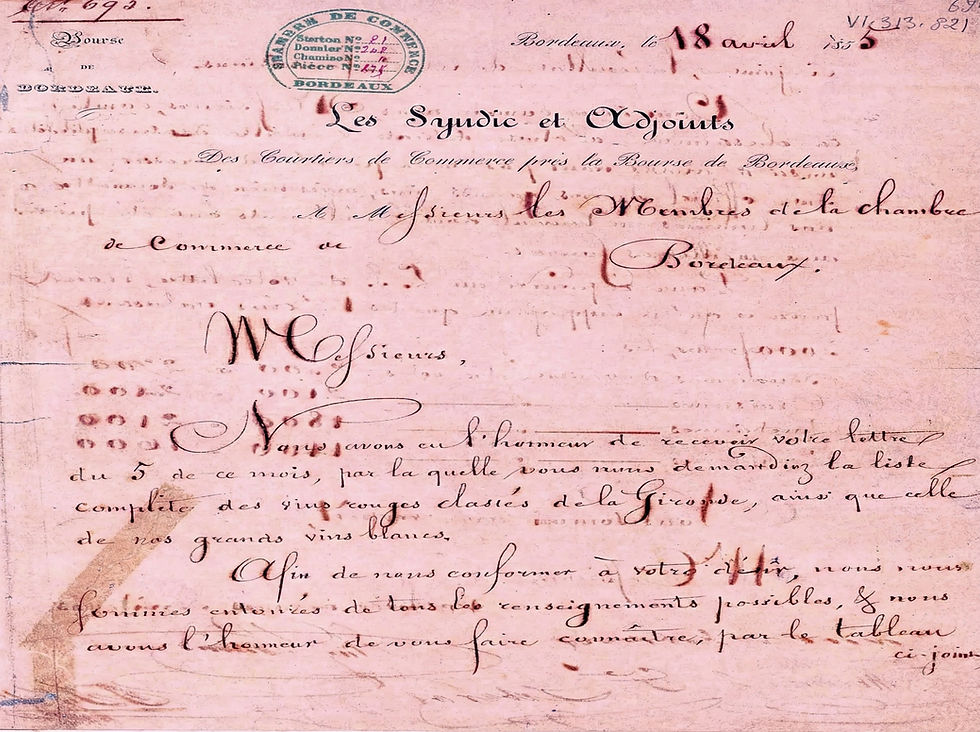

Start with market-level observability. Liv-ex, the leading fine wine marketplace, publishes the Liv-ex Fine Wine 1000, a broad benchmark tracking 1,000 wines across major regions (Bordeaux, Burgundy, Champagne, Rhône, Italy, and more). Liv-ex also reports rolling performance windows (1yr, 2yr, 5yr) that help investors understand where we are in the cycle. If you want to speak about wine investment with credibility, you need a source like this—not because indices are destiny, but because they provide a reference point for market direction.

What does wine add to diversification? In simple terms: a scarcity curve that steepens with time. Wine is one of the few assets where supply reduces through consumption and attrition, and where perfect provenance becomes rarer as years pass. That creates something I like to call “time-manufactured scarcity.” It doesn’t guarantee returns, but it creates a structural tailwind for the right wines, held correctly, bought at sensible levels.

Wine’s weakness is also what makes it investable: selection. The market is not one market. It is a hierarchy. The difference between a blue-chip producer with global liquidity and a pretty label with no exit market is the difference between an asset and a souvenir. This is why wine investment is closer to portfolio construction than it is to “collecting.” In practice, it means focusing on producers with deep demand, proven track records, and consistent price discovery—then buying when the cycle offers value rather than when social media offers excitement.

Another element worth stating plainly is that wine’s “return” is not free. Even in ideal conditions, you have storage and insurance, and you will have selling friction. Those carry costs are not a nuisance detail; they are part of the return equation.

Used properly, fine wine can play two roles in a diversified portfolio:

as a tangible diversifier whose value is tied to scarcity and global demand rather than corporate earnings, and

as a cycle opportunity asset, because wine markets can correct meaningfully and create entry points—something Liv-ex performance windows make visible.

Real estate: the cash-flow alternative, and why it behaves differently

If wine is a scarcity and brand asset, real estate is a cash-flow and replacement-cost asset. That difference matters.

In a diversified portfolio, real estate earns its keep through three traits:

it can produce income (rent),

it is often connected to inflation dynamics (rents and replacement costs), and

it can be financed, meaning leverage can amplify returns—while also amplifying risk.

The mistake is to talk about “real estate” as a single behavior. Residential and commercial behave differently. Prime and non-prime behave differently. Markets with strong transparency and deep liquidity behave differently than trophy assets with thin buyer bases. In some regimes, real estate behaves defensively; in rate shocks, it can behave like a long-duration asset and reprice fast.

For global comparability, investors often look at index providers such as MSCI. MSCI’s World Real Estate Index factsheets describe the index construction and provide standardized reference material, making it a useful benchmark lens even if your actual holdings are private properties.

Real estate’s most underappreciated feature is also its most dangerous: capital expenditure. Maintenance is not optional. Renovation cycles arrive whether you like them or not. Vacancy is the hidden volatility. And transaction costs—taxes, fees, time—are a permanent drag.

In a diversified portfolio, real estate is often the “serious alternative”: less romance, more balance-sheet discipline. It can serve as a stabilizer and income engine, but investors need to respect its sensitivity to rates and liquidity conditions.

Collectible cars: the romance asset with real carry costs

Collectible cars are a perfect example of why alternatives need frameworks. Done well, they can be exceptional stores of value. Done poorly, they are a maintenance bill that occasionally comes with a photograph.

Cars sit at the intersection of rarity, provenance, condition, and cultural relevance. Unlike wine, a car’s physical state can either be preserved or destroyed by neglect. Unlike watches, the carrying cost can be substantial. And unlike real estate, the market can be thinner and more fashion-driven.

The good news is that the classic car world has become more data-conscious. Hagerty’s Price Guide work and market analysis describe methodology and track thousands of models, reflecting how valuation increasingly relies on insured values, sales results, and observable market evidence rather than pure dealer narrative.

The key investor insight is that “the car market” isn’t one market. The liquidity, pricing, and long-run demand profile of an iconic reference model in concours condition is not comparable to a niche model with unclear collector depth. Here, more than anywhere, the exit market matters. Who will want this car in 10 years? Are there global buyers, or only local enthusiasts? Does provenance elevate it into a different tier?

As a portfolio sleeve, collectible cars tend to fit best as opportunistic alternatives. They can diversify, yes, but they demand expertise, patience, and a willingness to pay carrying costs. They are not a “set and forget” asset.

Watches: a post-bubble lesson in liquidity, spreads, and discipline

Watches are fascinating because they show both sides of alternatives in a single decade: the joy of scarcity and the brutality of cycles.

At the top end, watches have real liquidity. Certain brands and references can trade quickly, and the market has developed enough structure that index-style tracking exists. WatchCharts publishes market updates and index movement commentary that illustrate how the secondary market can experience multi-month declines, stabilization phases, and brand-level divergence. A market with observable pricing tends to mature faster, and that maturity is a friend to investors—because it reduces the space for fantasy.

But watches are also a textbook case of “luxury beta.” When liquidity is abundant, premiums expand. When the mood shifts, spreads widen and weaker references can become sticky to sell. WatchCharts’ own commentary notes periods of consecutive declines and later stabilization, a reminder that even collectible markets have regimes.

The investor’s edge in watches is rarely “predicting the next trend.” It’s more boring and more profitable:

buying references with durable demand,

insisting on condition, completeness, and documentation,

avoiding inflated entry points, and

accepting that selling friction is real.

In a diversified portfolio, watches can serve as a tactical diversifier—small, liquid enough at the top end, and global in demand. They work best when treated as an allocation with rules, not a hunt for dopamine.

Art: the hardest to index, the easiest to misunderstand

Art is often described as the ultimate passion asset. That’s true—and also precisely why investors misunderstand it.

Art does not behave like a typical financial market because its price formation is not continuous, its supply is deeply idiosyncratic, and its value depends on institutional validation, narrative, and collector psychology. The dispersion is enormous. A few artists and works can perform exceptionally; many pieces effectively flatline after costs.

For market-level grounding, the Art Basel & UBS research is one of the most widely cited references. Their Global Art Market materials report that global art market sales declined by 12% in 2024 to an estimated USD 57.5 billion, while the number of transactions rose—suggesting a softer high end and more activity at lower price points. That nuance matters: art can be active while aggregate value falls, because fewer trophy transactions have outsized impact.

They also note that both dealer and public auction values fell, with auctions particularly affected at the high end—again a reminder that art pricing is heavily influenced by a small number of blockbuster lots.

So what role can art play in a diversified portfolio? In my view, art is best understood as a legacy allocation and an access-driven market, where expertise and networks matter as much as capital. If you have the access, patience, and taste, art can store value and occasionally create extraordinary upside. If you don’t, it can become the most expensive illiquid position in your portfolio.

Art demands a certain psychological readiness: you have to be comfortable holding through silence, and you have to accept that selling is a process with timing, fees, and uncertain outcomes.

What a diversified “alternatives sleeve” can look like

Allocations are personal, and this is not advice. But we can still be concrete about structure. The most robust “alternatives sleeves” tend to avoid two extremes: the fully illiquid museum, and the fully trend-driven trading desk.

A conservative alternatives sleeve often anchors around real estate and fine wine: one leaning toward income and replacement-cost dynamics, the other leaning toward scarcity and global collector demand. This pairing can work because the return drivers differ meaningfully, even if both are tangible.

A balanced sleeve might add a controlled allocation to watches—ideally focused on references with deep liquidity and strong documentation standards—while keeping cars and art as smaller, opportunistic components. Watches can be helpful because, at the top end, the market can be surprisingly liquid and globally connected, while still offering a different behavioral pattern from equities.

A more opportunistic sleeve adds art and cars more meaningfully, but this is where the requirement for expertise and access becomes non-negotiable. Art market data underscores that high-end values can thin out sharply, affecting aggregate prices and liquidity—precisely when you might want optionality.

If there is one “professional” signal worth repeating, it’s this: sophisticated investors treat alternatives as strategic exposure. UBS’ family office data is a clear illustration that alternatives are not fringe in professional private wealth portfolios.

The three rules that keep investors out of trouble

1) Buy provenance before you buy upside

In wine, provenance is storage and documentation. In watches, it’s originality and papers. In art, it’s attribution and chain of custody. In cars, it’s history and condition. Provenance is not a detail; it is the asset.

2) Respect liquidity like you respect gravity

If you might need quick exits, build your sleeve around the more liquid segments: blue-chip wine with perfect storage, top-reference watches, and real estate you can realistically sell. Art and niche collectibles are wonderful, but they do not obey your timetable.

3) Carry costs decide who gets to be patient

Investing is often about being able to wait. Carry costs determine whether you can wait. They are the quiet force that turns “long-term conviction” into “forced sale.”

Conclusion: the point isn’t to be exotic

The best alternative investment sleeve doesn’t feel exotic. It feels intentional. It is built around return drivers you can explain, costs you can model, and liquidity you can live with.

Alternatives are not here to replace equities and bonds. They are here to give your portfolio something deeper: resilience, optionality, and in the best cases, a form of ownership that is both financially rational and culturally meaningful.

If you’d like to explore what a disciplined alternatives sleeve could look like—especially where fine wine fits into a diversified strategy—I’m happy to map it with you. The goal is not to own more things. The goal is to own the right things, for the right reasons, at the right level—and to let time do what time does best.

Frequently Asked Questions

What counts as an alternative investment?

Alternative investments typically sit outside public stocks and bonds. They include real assets (real estate), private markets, and collectible assets such as fine wine, art, watches, and cars—each with its own liquidity and pricing mechanics.

Do alternative investments reduce risk?

They can—but only when you diversify across different return drivers and stay disciplined on entry price. In stress periods, “luxury assets” can move together, so the real edge comes from selection, liquidity planning, and time horizon.

Why is fine wine considered an alternative asset?

Because supply is inherently constrained and often declines over time through consumption, while demand is global and increasingly institutional. The best wines behave less like consumer goods and more like scarce, traded assets—especially when provenance is perfect.

Is fine wine liquid? How do you sell it?

Liquidity is strongest in blue-chip producers, strong vintages, standard formats, and pristine storage conditions. Wine is typically sold via the secondary market—through merchants, brokers, and trading venues—where price discovery and exit routes are clearer.

What matters most for wine investment performance?

Selection and provenance. The best outcomes tend to come from wines with deep global demand and transparent, professional storage history—because buyers pay for confidence, not just labels.

What are the hidden costs of alternative assets?

Carry costs and friction: storage, insurance, servicing, fees, spreads, and time-to-sell. These costs don’t just reduce returns—they determine whether you can hold through a downturn without becoming a forced seller.

How much should someone allocate to alternatives?

It depends on objectives, liquidity needs, and time horizon. The best approach is to treat alternatives as a structured “sleeve” with rules—not as a collection of one-off purchases.

Curious about wine as an alternative asset ?

If you'd like to understand what's truly investable in fine wine - liquidity, timing, and portfolio construction - just book a private call with me now :

No obligation, just clarity on strategy, selection, and timing.

Comments