Mentzelopoulos & Château Margaux: A Contrarian Blueprint for Wine Investment (Part I)

- marclafleur3

- Jan 19

- 6 min read

Updated: Jan 23

1977: A Contrarian Purchase in a Depressed Bordeaux Market

In 1977, André Mentzelopoulos bought Château Margaux. Love at first sight, pure madness, or a visionary acquisition? At the time, Bordeaux was limping out of a double crisis: economic and qualitative. The great classified growths had fallen out of fashion, investors had turned their attention elsewhere, and many owners simply no longer had the means to invest in their vineyards and cellars.

Mentzelopoulos did what most investors would fear to do. He invested heavily in Château Margaux with no expectation of immediate profitability, in a market that was still sluggish, years before Bordeaux entered its new golden age at the end of the twentieth century. Five decades later, the outcome looks obvious. Back then, it didn’t. And that is precisely why this story matters.

Because beyond the romance of a château purchase sits a sharper question: what does a true contrarian opportunity look like when the crowd has stopped believing?

1970–1972 Bordeaux Boom: The Surge That Felt Unstoppable

The early 1970s weren’t just prosperous; they were euphoric. Europe was still surfing the long post-war expansion, and confidence had that peculiar taste it gets right before a turn: lending felt easy, discretionary wealth felt permanent, and symbols of status started to behave like assets. Wine, especially Bordeaux—Château Margaux and other First Growths in particular—became one of those symbols.

The New Buyers: London, Continental Europe, and the U.S. Awakening

London sat at the center of the heat. Fine wine had always been cultural currency there, but in those years it became something faster and louder: a race. The buyer pool widened. Young executives with bonuses, corporate gifting, collectors suddenly scaling up quantities. Continental Europe wasn’t far behind. The professional classes were normalizing luxury consumption, and Bordeaux fit perfectly into a new, aspirational grammar of refinement. The United States was still early in its fine-wine awakening, but the fuse had been lit. Importers and educators were already teaching Bordeaux to Wall Street and West Coast elites.

When Prices Detach from Reality

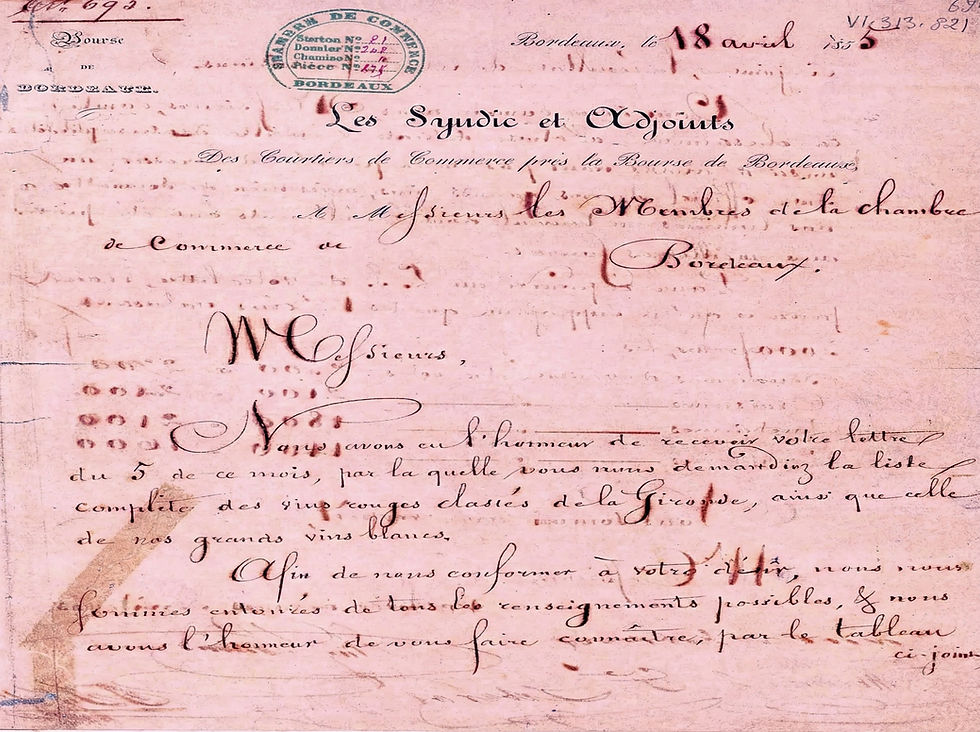

Prices began to behave in a new, exciting and bewildering way—the kind of behavior that, in hindsight, only ever has one destination. A contemporaneous trade document from Maison Sichel (dated February 1973, covering the 1972 vintage market) states that, depending on the appellation, prices for 1972 Bordeaux wines were “from 300% to 400% higher than 1970’s” and, of course, this would go on forever.

2020–2022 Fine Wine Boom: Sounds Familiar?

And what makes the early-1970s surge so instructive is how eerily it returned almost exactly fifty years later. In 2020–2022, a different shock produced the same euphoria. Lockdown-era savings, stimulus-fueled liquidity, and near-zero interest rates pushed capital out of cash and into anything finite, storied, and emotionally legible such as art, watches, handbags, and, increasingly, fine wine. With travel paused and experiences postponed, luxury objects became proxies for identity and reward. And with money cheap, holding non-yielding assets stopped feeling like an inefficiency and started feeling like common sense.

From Common Sense to FOMO

What began as common sense quickly turned into necessity, and, before you noticed, into pure Fear of Missing Out. Seasoned collectors and first-time buyers alike piled in, fully committed. In every bubble, there’s an acceleration phase, that final stretch when overconfidence becomes contagious. The “winning argument” stops being analysis and becomes mimicry: all my friends and colleagues think alike, so they must be right. And that’s when the truly strange ideas start to sound normal—repeated in specialist press, amplified by mainstream outlets, even carried by authority figures. Suddenly, everyone “discovers” that Champagne is a safe, high-yielding investment… certainly if you only look at a two-year chart. Memory shrinks when every light is green. Prices rise, and the crowd begins to treat last year’s increase as proof of next year’s increase. It no longer feels like a cycle, it feels like a new regime, one in which demand will keep compounding, and the ascent will somehow be permanent… right up until macro reality reintroduces gravity.

Since Late 2022: The Fine Wine Market Reset

Since late 2022, we’ve been living through the hangover phase of that boom: not a dramatic crash, but a severe reset. Prices softened. Allocations stopped moving. Expectations were repriced. What happened? In hindsight, the war in Ukraine reads like a psychological tipping point: the world order began to wobble, and so did sentiment. But bubbles rarely deflate because of one event. What breaks the spell is usually a convergence, a chain of pressures that, together, puncture the comforting illusion of permanence.

The loss of Russian buying power mattered, as did the disruptions and dislocations in the supply chains that followed sanctions. China’s post-Covid recovery proved slower and uneven. An overpriced 2022 En Primeur campaign bruised confidence. Cultural headwinds stiffened in the West. And as global markets rebounded through 2023 and 2024, and interest rates made traditional investments attractive again, capital began to flow away from alternative assets like wine. Add to that a darker geopolitical sky, and investors naturally turn cautious, holding cash, delaying discretionary purchases, and no longer confusing yesterday’s momentum with tomorrow’s certainty.

1973–1974 Bordeaux Crash: Why the Market Broke

If the boom was fueled by money, credit, and psychology, the reversal came from a brutal combination of external shock and wine’s own unforgiving realities, the kind of moment when macroeconomics and Mother Nature conspire to end the party.

Oil Shock, Liquidity, and a Sudden Loss of Confidence

If the war in Ukraine may rank amongst the external factors that initiated the current correction cycle, the first oil crisis, five decades back, acted in a similar, perhaps even more brutal way, hitting confidence, spending, and, most decisively, liquidity. Credit lines and buying appetite—that winning combination that until yesterday was the flavor of the day—disappeared under a veil of uncertainty.

Poor Vintages as a Market Catalyst

Inside the bottle, nature delivered the second knockout blow. The euphoria of the boom ran straight into a run of punishing vintages, and quality—always the final judge—couldn’t justify the prices. A Decanter retrospective recalls that 1973–74 turned “catastrophic” even for top-end Bordeaux: after an “unprecedented speculative boom” around 1970 and 1971, the market “collapsed when international support vanished,” and the 1972 vintage punctured the illusion by revealing how poor even these wines could be. It’s worth remembering the context: cellar work was already serious, often brilliant, but it simply did not have today’s arsenal—precision viticulture, stricter selection, gentler extraction tools, temperature control, and the accumulated experience of another half-century. Poor vintages are still poor, but they are managed differently now, and the outcomes can be dramatically less brutal.

The Violence of the reveral: From Quadrupling Prices to “Unwanted Orphans”

The scale of the reversal is captured in later commentary from Liv-ex’s co-founder (quoted by Decanter): Cru Classé prices quadrupled between 1970 and 1972, only to see those increases erased by 1974. And the trade’s own language turned bleak. A later reference to Maison Sichel’s 1974 reporting calls the 1974s “the unwanted orphans of a shattered marketplace.”

Ginestet Ownership of Château Margaux: Setting the Stage for the 1977 Sale

To understand why Château Margaux could be sold in 1977, we need to rewind to the Ginestet era. Fernand Ginestet made his fortune on the Place de Bordeaux, and the family’s identity was first and foremost that of a major merchant house—built on distribution, relationships, and trade. In parallel with the rise of Maison Ginestet, they gradually accumulated shares in Château Margaux until, around 1950, they secured full ownership. Château Margaux’s own history credits them with patiently reorganising the vineyard during their tenure.

Merchants Turn Speculators: Credit Lines, Inventory, and Repayments

But the same cycle that inflated Bordeaux in 1970–1972 also planted the seeds of what followed. As the boom intensified, many merchants began behaving like speculators, buying to hold, not simply to sell, often financed through bank credit lines. It felt like an easy bet in a market convinced that demand and prices would rise indefinitely. Then sentiment turned, buyers looked elsewhere, and the music stopped. With liquidity drying up, the mechanics of the trade became unforgiving: inventory sat, repayments came due, and what had looked like clever positioning revealed itself as leverage with nowhere to hide.

1972–1974 ‘Unsaleable’ Vintages and a Capital-Hungry First Growth

At the same time, the wine itself delivered the final blow. The unsaleable 1972, 1973, and 1974 vintages pushed Pierre and Bernard Ginestet into a desperate situation. Trying to keep the merchant house afloat, they watched Château Margaux, the family’s jewel, turn into a weight. Owning a First Growth sounds glorious, but it is also a capital-hungry machine, demanding constant investment in vineyards, people, and infrastructure precisely when cashflows are under pressure. Sacrificing one asset to save the mothership merchant house became inevitable.

To be continued…

Comments